When publishing dates 'go wrong'

- Peter Crush

- 1 day ago

- 5 min read

Knowing which Jonathan Capes impressions you have is normally a pretty simple affair – but occasionally, some publishing date mistakes still slipped through the net

In his 1963 short essay ‘How to Write a Thriller,’ Ian Fleming gives a rare nod to the book production process at Jonathan Cape – describing the people there as a “sharp-eyed bunch.”

However, they weren’t always quite as sharp-eyed as Fleming gave them credit for.

For as collectors of the Ian Fleming first editions will know, many errors (and typos), still appeared on the first galley pages and uncorrected proof editions, and many of these still crept through, to appear in the final finished books.

But it wasn’t just in Fleming’s manuscripts where the ‘sharp-eyed bunch at Cape’ missed mistakes. There were also errors introduced into the books that Fleming didn’t actually write – but which production assistants at Cape did themselves.

These are the mistakes that can be found on some of the blurbs on the flaps, on the DJ jacket back panels (typically the reviews), and even where Cape lists the chronology of the previous books. Some real howlers include some of the publishing orders being mixed up, Jonathan Cape actually spelling its own name wrong, and titles of the books being incorrectly spelled too.

Examples of these include:

The verso half titles in later books begin to miss out the comma in ‘From Russia, With Love’ while there is no dot in Dr No.

The 4th print of Moonraker lists ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ as ‘Diamonds Are For Ever’ on the half-title verso.

The 6th, 7th and 8th prints of Moonraker have ‘Ltd’ appearing twice on the copyright page.

The 1974 7th print of Diamonds Are Forever fails to list The Man With the Golden Gun on the verso of the half title (while the dust-wrapper does has it, but the order of the last two books are transposed).

The 7th impression of Goldfinger misses out Live and Let Die in the list of previous books on the verso of the half title.

The 6th printing of For Your Eyes Only misses out Golfinger and Live and Let Die on the verso of the half title. They are reinstated on the 7th impression of For Your Eyes Only, but tagged on at the end (after Octopussy), meaning the list of previous books are not in chronological order.

OK, in the grand scheme of things, these aren’t massive problems – and are kind of humorous really.

But the one thing modern-day collectors kind of rely on being correct – especially those who seek to own a copy of each edition – is the colophon/copyright information.

In particular, it’s the impression information – such as whether this book is a first, second, third, fourth etc…

But, once again, even those ‘sharp eyed bunch’ at Cape didn’t always get this right either – and it can mean people could think they are missing an impression , or have their chronology of books wrong.

Live and Let Die – the 'missing impression'?

To explain what I mean, we only need to look at the printing history of the second book in the James Bond series – Live and Let Die.

It was while researching a previous blog on first and last impressions (and how many impressions there were in-between), that a collector I know got in touch to say he had most of the Live and Let Die impressions apart from the 8th impression.

He based this (naturally enough) by having both a 7th and 9th impression, and was missing an 8th.

Above left - a 7th impression Live & Let Die, and (above right) a 9th impression Live & Let Die

Looking at his 1963-dated 9th print (to see when the 8th was made), he quite naturally presumed his missing 8th print was reprinted in 1962 – as per how the 9th print set this out (see picture above).

His 1964 10th impression further gave him confidence that he was missing a 1962 8th printing, because (as shown on the picture left), his 10th print had the same publishing information: that the 9th was ‘reprinted in 1963’ and the one before it (ie the 8th), was ‘reprinted in December 1962’.

So...his missing 8th print? A 1962 book it was then.

So-far-so-simple!!

But look at this.

I decided I would try and help him find his missing 8th, but I was surprised to find that when I ‘did’ find one, it’s publishing information was very different from what I expected.

As can be seen in the picture here, the genuine 9th print colophon reads that it was printed in 1963! (not 1962). It claims there was no printing in 1962 at all, with the previous 7th print being printed in 1960. As can quite clearly be seen, there was a three-year gap between the 7th print in 1960 and the 8th, which it says was printed in 1963.

This seems quite definitive – that the 8th print was printed in 1963 – not 1962 after all.

Here are the 7th, 8th, and 9th impression books all in a line (left to right), so you can see the differences more clearly:

So here’s the thing.

Why do the next two impressions – the 9th and the 10th prints – both say the 8th print appeared in December 1962?

And why do both the 9th and 10th prints (here is a 10th print for reference - see left), both say that it was the 9th print of Live & Let Die (not the 8th), that appeared in 1963?

An answer?

If we turn to Gilbert, there is an interesting entry about the 9th print.

Bibliographer Jon Gilbert says the 9th print was ’aborted’ early in the print run and is ‘not accounted for in the otherwise detailed Jonathan Cape book production ledger’ (p66). He claims only a couple of 9th prints have ever been observed.

By the time the 10th print comes out (see above), the colophon references a ninth print in 1963, and subsequent impressions all no longer reference this 9th printing. (So it appears that the 8th printing is at least correct from a printing time-line point of view)

Are there any more examples like this?

It can be incredibly confusing for collectors if something as simple as the dates of previous impressions are not consistent from edition to edition.

If collectors don’t have all of them to compare against, they can quite easily assume that a specific impression doesn’t exist at all, or lead them to mis-catalogue their own collections.

But, this is by no means the only example of this...

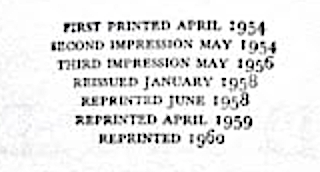

On the third impression of Dr No’s, the copyright page lists the 3rd printing simply as ‘Third Impression 1958’ – even though the actual publication date was April 1959.

Subsequent impressions correctly state this (see pic left).

But anyone with only a third print may think two impression exist in 1958, when if fact, only the second impression exists for that year.

Talking of Dr No, there is a theory that the 11th impression (1982) simply doesn’t exist at all, even though the 12th impression (1983) lists it (to my knowledge that is, as I'm missing this book - so I haven't physically seen the copyright information on a 12th print).

In one other example, on Diamonds are Forever, the colophon states that the third printing was 1959.

In actual fact the third printing was issued in 1960 - but subsequent impressions (see pic below), still have it down as being in 1959. This continues on each impression up to the final 8th impression, so while it's technically wrong, at least the error is consistent!

Conclusions:

While I'm not suggesting all of the Jonathan Capes need approaching with caution (99% of the time their printing information is correct) - these examples do at least show that even Cape misprinted its own impression information, and it can still cause collector confusion 70 years later!

These are the examples I've come across, and there could well be other small publishing information errors that are out there.

Not all is always what it seems!

Comments